The first day of February 2017 was a very good one for Rex Tillerson.

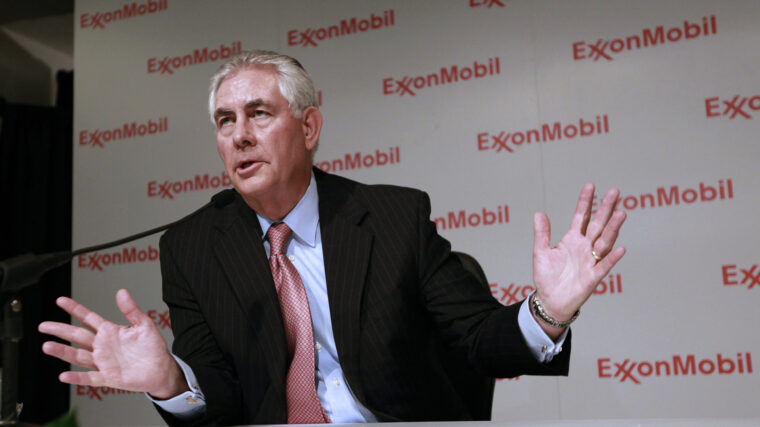

That afternoon, the U.S. Senate voted 56-43 to substantiate him to be secretary of state. The lately retired ExxonMobil Corp. CEO was sworn in on the White Home just a few hours later along with his spouse and President Donald Trump at his facet.

However there was one other vote that day that was consequential in Tillerson’s profession — and for the political fortunes of Exxon, which had sizable holdings in Russia and investments in different undemocratic nations. The Home of Representatives voted to kill an anti-corruption, pro-transparency rule that the oil {industry} — and Tillerson personally — had been preventing in several types for years. The Senate adopted go well with just a few days later.

The rule, mandated by an modification to the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Avenue Reform and Shopper Safety Act and issued by the Securities and Alternate Fee, would have required oil, gasoline and mining firms listed on U.S. inventory exchanges to publicly disclose their funds to governments the place they function, each abroad and domestically.

The modification’s bipartisan co-sponsors, Sens. Ben Cardin, D-Md., and the late Richard Lugar, R-Ind., believed it was within the U.S.’ curiosity to assist the billions of individuals dwelling in resource-rich nations to cease their rulers and elites from diverting oil, gasoline and mining wealth from public coffers to counterpoint themselves. They thought disclosing firm funds to governments would undermine the secrecy that permits kleptocracy to flourish.

Transparency and anti-corruption teams worldwide equivalent to Oxfam, the FACT Coalition, Publish What You Pay and EarthRights Worldwide supported the measure, and Canada, Norway and the European Union rapidly adopted practically an identical guidelines.

However within the U.S., the Cardin-Lugar modification set off a relentless, high-pressure lobbying and authorized drive led by Exxon, Chevron Corp. and the American Petroleum Institute that may stretch over a decade. They challenged three variations of the rule within the courts and Congress, and on the SEC, the place one former commissioner stated he spent “half his time” with their lobbyists.

On the time, oil {industry} advocates argued that the worth tag for implementing the unique model of the SEC rule can be an excessive amount of of a burden for firms; the company estimated it could have an effect on 1,100 corporations and initially value them a complete of $1 billion. The {industry} additionally asserted that the rule would put U.S. oil firms at an obstacle, doubtlessly giving rivals a monetary edge when negotiating offers.

As extra firms complied with Cardin-Lugar-style disclosure guidelines in different nations, there was little proof to help these dire predictions, transparency advocates stated. However within the U.S., the epic lobbying blitz carried on, and in December 2020, throughout the waning days of the primary Trump administration, the {industry} bought the end result it wished. The SEC voted 3-2 to approve a weaker rule that now not required disclosure of funds by contract and included extra exemptions from having to report in any respect.

In most jurisdictions, pure assets are managed by the state on behalf of its residents.

— Ian Gary, government director of the FACT Coalition

The diminished rule’s inadequacies — and relevance — grew to become clearer this 12 months, the primary 12 months firms disclosed funds to the U.S. and international governments.

Transparency advocates stated the watered-down rule nonetheless had worth and can “additional improve the worldwide norm of revealing oil and mining firm funds to governments,” Ian Gary, the manager director of the Monetary Accountability and Transparency (or FACT) Coalition, advised ICIJ. “In most jurisdictions, pure assets are managed by the state on behalf of its residents. Individuals have the best to know fundamental monetary details about the sale of those non-renewable property.”

However the present rule additionally permits firms to go away out key particulars. For instance, Exxon, Chevron and different corporations together with Transneft, a Russian state-owned firm, are companions within the Caspian Pipeline Consortium. CPC pays a whole bunch of hundreds of thousands of {dollars} in taxes and fines to Russian governmental authorities. These taxes assist maintain the Russian economic system, enhance arms manufacturing and pay state officers’ salaries and pensions — thereby aiding the Russian conflict effort in Ukraine.

But of their first disclosures, filed with the SEC, neither firm reported any funds to Russia. Beneath the rule handed in 2020, the businesses don’t need to report funds made by a three way partnership that they don’t straight function.

In an announcement to ICIJ, Sally Jones, a senior media adviser for Chevron, stated the corporate is “dedicated to moral enterprise practices, working responsibly, conducting its enterprise with integrity and in accordance with the legal guidelines and laws of every of the jurisdictions through which it operates.” Exxon didn’t reply to requests for remark.

The story of this drawn-out battle towards a fundamental anti-corruption effort is a part of Caspian Cabals, an investigation led by the Worldwide Consortium of Investigative Journalists and 26 media companions into the rise of a essential pipeline within the Caspian Sea area and the Kazakh oil fields that feed it.

The 2-year investigation is predicated on tens of 1000’s of pages of confidential emails, firm shows and different oil {industry} data, audits, court docket paperwork and regulatory filings, in addition to a whole bunch of interviews, together with with former firm staff and insiders. Caspian Cabals reveals how Western oil firm cash has empowered anti-democratic actors in Kazakhstan, bolstered the neighboring regime of Russian president Vladimir Putin and enriched regional elites. That features Nursultan Nazarbayev, who led Kazakhstan from 1991 to 2019, throughout which a number of members of his household amassed multibillion-dollar fortunes.

The struggle over the Cardin-Lugar rule confirmed the lengths to which some U.S. oil firms and their allies have been prepared to go to thwart larger transparency and to keep away from nearer scrutiny of their relationships with autocrats and kleptocrats. “It’s no marvel that Large Oil and its lobbyists fought tooth and nail to dilute U.S. laws on fee transparency,” stated Jana Morgan, the director of Publish What You Pay-US from 2013-2017. “They know that transparency exposes wrongdoing and holds each firms and governments accountable.”

The case for daylight

The push in Congress to get oil, gasoline and mining firms to reveal their funds to governments dates again to 2008. That 12 months, Lugar, then the rating member on the Senate International Relations Committee, despatched a dozen committee staffers to 21 nations to evaluate anti-corruption efforts in resource-rich nations, in response to Jay Branegan, a senior staffer on the Senate panel who labored with Lugar.

“We discovered loads of examples of the ‘useful resource curse’ — nations with substantial oil or mineral deposits that have been nonetheless doing poorly economically,” Branegan recalled. In some nations like Nigeria, the Senate committee employees members noticed that poverty elevated after the invention of oil. They compiled their findings in a 119-page report titled “The Petroleum and Poverty Paradox: Assessing U.S. and Worldwide Neighborhood Efforts to Struggle the Useful resource Curse.”

“This ‘useful resource curse’ impacts us in addition to producing nations,” Lugar wrote in a letter connected to the report. “It exacerbates international poverty which is usually a seedbed for terrorism, it dulls the impact of our international help, it empowers autocrats and dictators, and it may well crimp world petroleum provides by breeding instability.”

Cardin, who served on the International Relations Committee with Lugar and now chairs it, advised ICIJ that the Cardin-Lugar modification grew out of that analysis. “For a very long time we’d been following corruption amongst sure nations with the extractive industries the place the earnings from the extractive industries have been going to the leaders of the nation or the ability folks of the nation, and to not the residents,” he stated.

The lawmakers believed extra transparency would make it tougher for international leaders to skim off {industry} funds. Additionally they believed it could assist to stabilize markets and defend traders.

This ‘useful resource curse’ … empowers autocrats and dictators, and it may well crimp world petroleum provides by breeding instability.

— Senator Richard Lugar, co-sponsor of the Cardin-Lugar modification

Advocates for fee transparency additionally burdened the unfavourable impacts of corruption on nations like Equatorial Guinea, a serious oil-producing nation in Central Africa. Its vp, Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, who can be a son of the nation’s longtime chief, relied partly on cash from Western oil firms, together with Exxon and Chevron, to amass greater than $300 million in property, in response to U.S. prosecutors. Whereas about 75% of its inhabitants of lower than 2 million lived in poverty, he owned a $30 million dwelling in Malibu, a fleet of luxurious vehicles together with Ferraris, Lamborghinis and Bentleys, and one of many largest collections of Michael Jackson memorabilia that included a $275,000 crystal-covered glove. Obiang additionally had a $124 million six-story mansion in Paris that contained a $1.8 million Louis XV desk, a Rodin sculpture and a dozen Fabergé eggs.

The stolen monies ought to have been used for training, roads and hospitals just like the one Tutu Alicante’s sister went to in Equatorial Guinea in 1996 for an ectopic being pregnant. Alicante, now the manager director of the human rights advocacy group EG Justice, recalled at an October occasion with transparency teams that the hospital had neither electrical energy nor a health care provider and his sister bled to dying. “Throughout these years my nation, Equatorial Guinea, was known as ‘the Kuwait of Africa’ due to the quantity of oil and gasoline that was being produced. But my sister, like a whole bunch of ladies in my nation, … was nonetheless dying … due to not ailments or any diseases, however relatively on account of entrenched, grinding poverty and inequality that was manufactured by the autocratic authorities in my nation, supported by oil firms.”

In 2010, because the Cardin-Lugar proposal gained momentum on Capitol Hill, Tillerson, then Exxon’s CEO, flew to D.C. for a half-hour assembly with Lugar.

“Tillerson was the one oil firm government to return to Senator Lugar’s workplace personally to foyer towards the proposed laws,” recalled Branegan. “The truth that the CEO of a large international company would personally foyer the senator confirmed us how significantly the {industry} regarded the problem.”

Branegan stated Tillerson repeated “most of the oil {industry}’s arguments and likewise stated that it could harm Exxon’s relations with Russia.”

Tillerson and Exxon had in depth ties to Russia and Putin. Earlier than he grew to become CEO in 2006, Tillerson was a director of Exxon Neftegas, an offshore firm within the Bahamas that was on the coronary heart of Exxon’s shut enterprise dealings with Russia, in response to leaked paperwork from the Bahamas company registry obtained by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared with ICIJ in 2016. Tillerson ended his affiliation with Neftegas in 2001, an organization spokesperson stated.

In 2011, Tillerson attended the announcement in Sochi, Russia, of a $3.2 billion deal between Exxon and the Russian oil firm Rosneft to open oil and gasoline manufacturing within the Arctic Ocean. On the signing ceremony, then-Prime Minister Putin stated, “The size of the funding may be very massive. It’s scary to utter such large figures.” The next 12 months, Exxon introduced a $500 billion three way partnership with Rosneft, and in 2013, Putin awarded Tillerson the Order of Friendship, a state ornament for foreigners whose work improves their nations’ relations with Moscow.

Makes an attempt to achieve Tillerson have been unsuccessful.

Lugar advised Tillerson throughout their half-hour assembly in 2010 they must conform to disagree, Politico reported. Cardin-Lugar was enacted that 12 months as Part 1504 of the Dodd-Frank monetary reform regulation. A phalanx of lobbyists for the oil {industry} and its allies had tried to dam efforts to connect it to Dodd-Frank and, when that failed, ultimately took authorized motion and stepped up their lobbying marketing campaign.

“To discredit and weaken our place, they used each excuse possible,” Cardin advised ICIJ. “They have been very aggressive within the Senate lobbying towards 1504. It was one of many heaviest lobbying efforts I’ve ever seen.”

Large Oil goes to court docket

The SEC took two years to show Cardin-Lugar into laws, which the oil {industry} and enterprise allies rapidly challenged.

In October 2012, the American Petroleum Institute, the chief oil {industry} lobbying group, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and two different commerce teams with robust oil and enterprise ties filed a lawsuit towards the SEC. They argued that the company did not adequately weigh the rule’s prices and advantages, and that the rule would reveal delicate inside enterprise info.

Eugene Scalia, a companion on the white-shoe agency Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher in Washington and a son of then-Supreme Court docket Justice Antonin Scalia, argued the case in court docket. By then, the youthful Scalia had already gained a case towards a special Dodd-Frank company rule and had notched victories towards different SEC laws.

In 2013, a U.S. District Court docket in Washington dominated in favor of API and the opposite plaintiffs, which despatched supporters of the rule again to the drafting board to redraft it.

Michelle Harrison, deputy common counsel with EarthRights Worldwide, who was closely concerned in backing the unique SEC rule, advised ICIJ that the revised model was additionally “robust” and supported by many anti-corruption and pro-transparency teams. The SEC authorised it in mid-2016. However as soon as Trump took workplace in early 2017, the oil {industry} and enterprise allies went again on the offensive.

In a letter dated Jan. 31, 2017, a day earlier than the Home voted to nullify the rule, then-API President Jack N. Gerard advised lawmakers the rule was overkill. He argued that the 1977 International Corrupt Practices Act already forbade firms from bribing international officers and that the brand new rule, mixed with these prohibitions, would harm U.S. corporations’ aggressive place. He complained, too, that the rule was not per the company’s mission of defending traders and investigating fraud, and steered the SEC unnecessarily took on a “social agenda subject.”

An API spokesperson declined to remark, saying the SEC rule is now not an lively subject for the group.

In an opinion piece in The Hill, revealed the identical day Gerard despatched his letter, Cardin and Lugar, who by then was now not within the Senate, disputed the argument that the disclosures would reveal delicate firm info. They identified that many countries had embraced an identical rule and that some massive oil firms like BP PLC, TotalEnergies SE and Shell PLC, plus some Russian oil giants together with Gazprom and Rosneft, had already complied with disclosure necessities abroad.

Paul Pelletier, a former senior Justice Division official who served as appearing chief of the Prison Division’s fraud part, took subject with the {industry}’s argument that current anti-bribery legal guidelines made additional disclosure pointless.

“The [Foreign Corrupt Practices Act] forbids bribery by U.S. corporations abroad to win enterprise however doesn’t require disclosure of funds to international governments by U.S. firms,” he advised ICIJ. The oil {industry} missed “the advantages of extra transparency because the rule initially supposed.”

Transparency advocates level to Ghana as successful story. Funds knowledge influenced lawmakers there in 2016 to alter royalty charges and capital good points tax guidelines for oil and gasoline manufacturing, which helped enhance authorities revenues, in response to Rob Pitman, senior governance officer with Pure Useful resource Governance Institute.

In Europe, the place the unique Cardin-Lugar proposal impressed nations to undertake related disclosure guidelines, proof was additionally beginning to emerge that undermined the {industry}’s competition that undermined the {industry}’s declare the price of implementing Part 1504 was burdensome. French oil large Whole would later report that its annual compliance prices in relation to a transparency directive and an accounting directive have been about $200,000, a 2020 evaluation by Publish What You Pay confirmed.

The [Foreign Corrupt Practices Act] forbids bribery by U.S. corporations abroad to win enterprise however doesn’t require disclosure of funds to international governments by U.S. firms.

Paul Pelletier, former senior Justice Division official

Oil lobbyists and their enterprise allies gained the argument, although, with the one viewers that mattered. They turned to 3 buddies in Congress: Rep. Invoice Huizenga, R-Mich., the late Sen. James Inhofe, R-Okla.; and then-Senate Banking Committee Chairman Mike Crapo, R-Idaho. The lawmakers employed a legislative software known as the Congressional Assessment Act to overturn the rule in February 2017 within the Home and Senate. Trump signed the regulatory disapproval measure quickly after.

Crapo and Huizenga didn’t reply to requests for remark.

At his affirmation listening to just a few weeks earlier, Tillerson was requested repeatedly about his dedication to transparency and preventing corruption.

He advised lawmakers: “Throughout my tenure as chairman and CEO, ExxonMobil strongly supported efforts to extend the transparency of presidency income from the extractive industries.”

A number of senators additionally requested him concerning the vitality firm’s operations in Equatorial Guinea. In 2004, the 12 months Tillerson grew to become a director and president of Exxon, it was one among 4 oil firms questioned by the SEC over their funds to the Obiang authorities. The inquiry adopted a 2004 Senate subcommittee report on cash laundering at Riggs Financial institution, the place Obiang and his members of the family had a number of accounts. The report stated Exxon began an oil distribution agency in Equatorial Guinea in 1998, 15% of which was owned by Abayak S.A., an organization managed by President Obiang, his spouse and son. Throughout his affirmation listening to, Tillerson stated a congressional inquiry didn’t discover proof that Exxon dedicated wrongdoing.

He went on to say the corporate’s contracts with international governments have been no totally different than ones used for tasks on federal land within the U.S. “There’s royalty and there are taxes paid to the … Treasury,” he stated. “What the federal government does with these monies as soon as the corporate pays these is as much as the federal government.”

An industry-friendly rule

After Congress killed the second model of the SEC rule, the company started to revise it as soon as extra because it was required to do by regulation, a course of that took practically three years and sparked one other wave of lobbying.

Former commissioner Robert Jackson, who served on the company from 2018 till early 2020, advised ICIJ he spent half his time assembly with lobbyists for the oil firms. He stated the {industry} and its allies approached him with a “sense of authorized entitlement.” They appeared to suppose — incorrectly, in Jackson’s view — that Congress killing the earlier model “mandated a weaker rule.” Assured the courts would again their place, “the Chamber typically threatened to sue the SEC,” he recalled. (A spokesperson for the Chamber declined to remark.)

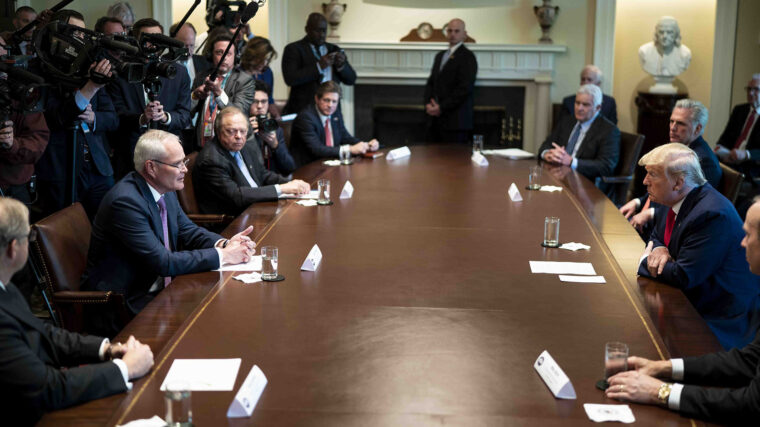

The rule remained a high precedence for Exxon executives. Darren Woods, who took over as CEO of Exxon in 2017, even traveled to Washington in November 2018 to satisfy with then-SEC Chair Jay Clayton. Clayton didn’t reply to a number of requests for remark.

By 2020, the SEC had drafted a 3rd model that was rather more favorable to the {industry}. Cardin and different transparency advocates criticized it as too lax. Jackson, who labored on it however left the SEC in February that 12 months, stated the ultimate rule was so watered down it offers “virtually no significant daylight.”

A key sticking level was the best way the rule outlined precisely what oil firms have been required to reveal about their international funds. It exempted disclosures of oil funds beneath $150,000, the place transparency teams say corruption typically happens. And relatively than having to itemize their funds by every contract or mission for larger transparency, firms have been required to report mixture funds solely by nation or political jurisdiction. The rule additionally added two exemptions for “conditions through which a international regulation or a pre-existing contract prohibits the required disclosure.”

On Dec. 16, 2020, the fee authorised the industry-blessed rule by a vote of 3-2, with Jackson’s successor, Caroline Crenshaw, and fellow commissioner Allison Herren Lee dissenting.

“Ultimately, it’s onerous to grasp who we’re serving with this last rule,” Lee stated in an announcement that day. “We’re not effectuating Congress’s intent in passing Part 1504. We’re not making certain sufficiently granular disclosure to allow residents to fight corruption. We’re not offering traders with the knowledge that’s materials to their funding and voting selections. We’re not heeding the quite a few calls from issuers who’ve requested us to harmonize our guidelines with the worldwide normal. And, most sadly, we’re not taking the chance to additional the SEC’s and the US’ custom as leaders within the struggle towards international corruption.”

The rule takes impact

Practically 15 years after the Cardin-Lugar modification was enacted, Exxon and Chevron launched their first disclosures in September.

In its Part 1504 submitting, which covers fiscal 12 months 2023, Exxon reported that its largest fee went to the United Arab Emirates ($7.4 billion), adopted by Indonesia ($4.6 billion). It paid the U.S. $2.3 billion. Exxon additionally stated it paid $12.2 million in taxes and charges to authorities entities in Kazakhstan. Most of it went on to a authorities tax collector and the remaining to the state-owned pipeline firm.

Chevron listed solely a complete fee for every nation. Its largest funds went to Australia ($4 billion) and Nigeria ($3.2 billion). It stated its funds to Kazakhstan totaled $152.7 million.

Neither Exxon nor Chevron reported any funds to Russia for 2023 regardless of their stakes within the Caspian Pipeline Consortium, which pays Russia taxes and fines. In 2022, CPC paid about $321 million to Russian authorities, together with $96 million in taxes and charges to the federal authorities. It additionally paid a $98.7 million superb on account of an August 2021 oil spill.

The businesses don’t need to report funds made by a three way partnership that they don’t straight function, nor have they got to reveal how a lot they reimburse the operator for his or her share of the funds to governments. Exxon and Chevron didn’t reply to questions on their disclosure filings.

Zorka Milin, FACT’s coverage director, advised reporters at a press briefing just a few weeks after their launch that the disclosures confirmed Large Oil was not invincible. “On this subject they threw every part towards it. That they had high-powered attorneys and lobbyists. They even dragged the Chamber of Commerce into it. And sure … they did have some authorized and political victories alongside the best way, however despite all of it … we’ve bought these disclosures which they by no means wished to see the sunshine of day.”

[In] spite of all of it … we’ve bought these disclosures which they by no means wished to see the sunshine of day.

– Zorka Milin, FACT Coalition coverage director

Aubrey Menard, Oxfam America’s senior coverage adviser for pure useful resource justice, additionally described the disclosures as “a serious victory for civil society and really revealing concerning the {industry}’s funds.” However she advised ICIJ they’ve “some vital gaps on account of Large Oil’s decade-long marketing campaign to water down the ultimate rule.”

The SEC rule doesn’t require the businesses to report funds for tasks or jurisdictions inside nations, she continued, making the disclosures much less helpful. “It does little good to have one mixture quantity for all funds lumped collectively so that you simply can’t see which is for what mission or to what state,” Menard stated. “It makes it unimaginable to research the utility of a single mission or whether or not residents are receiving what they need to in trade for his or her pure assets, or for traders to judge a mission’s value and threat.”

Menard famous critically that in its disclosure, “Exxon features a lengthy preamble about all of the funds that they’re making that they aren’t required to reveal below the SEC rule, together with taxes, charges and duties paid to native, state and federal governments. However since they’re declining to reveal this info, are we simply purported to belief them on these?”

The present model of the disclosure rule is probably not the final one. The company has included it on its rulemaking agenda for a number of years as a attainable goal for overview however hasn’t adopted via.

Cardin, who’s retiring when his time period ends in January, stated he has not given up on strengthening the rule. In a September letter, Cardin pressed SEC Chair Gary Gensler on the company’s failure to maneuver ahead.

The present rule is the regulation, Cardin wrote, however so is Dodd-Frank, and “I’m gravely involved the SEC is failing to satisfy its authorized obligations below Part 1504.” An SEC spokesperson advised ICIJ the company “doesn’t touch upon what regulatory actions the Fee could take sooner or later” past the general public rulemaking agenda.

The model that’s now in impact, Cardin advised ICIJ, can’t be allowed to face. The laws are “higher than nothing, however they defend the oil firms and the corrupt leaders.”

Contributors: Annys Shin (ICIJ)